- Jan 15, 2026

Facial Paralysis During Surgery: The Critical Role of Intraoperative Neurophysiological Monitoring

- Aisha K. Kazi

- ionm, neuromonitoring, neurophysiology, Blogs, cranial nerves, ENT, neuroscience

- 0 comments

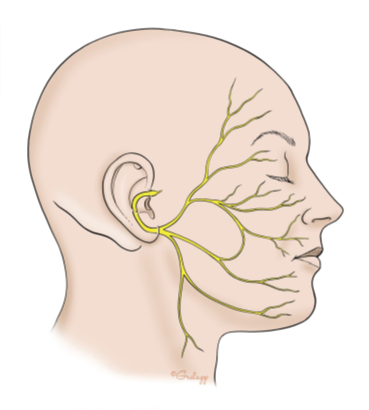

Facial Paralysis has long been recognized as a clinical shortcoming in facial and neck surgery, particularly in otolaryngology, neurosurgery, and plastic surgery. Surgical procedures themselves are already considered frightening, and to wake up from anesthesia to the surprising new complication can be regarded as life-altering for those with possible permanent facial paralysis. The condition goes further than a physical limitation– it can impact a patient’s quality of life. To tackle the issue overall, it is important to first understand the anatomy behind the condition. Facial paralysis is almost always related to the facial nerve, also known specifically as Cranial Nerve (CN) VII. The nerve bilaterally hooks around each ear and branches across the face, forming a spider-web-like pattern that innervates over 35 muscles, laying the framework for facial movement. Regardless of whether the condition is a surgical complication or a congenital issue, CN VII is the most important factor in facial expression.

Anatomy of the Facial Nerve (Jackler & Gralapp)

Classification and Causes

Despite the astounding innovation occurring in the medical field throughout the decades, the issue of facial paralysis during surgery is still present. The injury presents itself in one of three ways: neuropraxia, axonotmesis, or neurotmesis. The classification depends on the severity of the facial nerve injury. Neuropraxia, the mildest form, is a temporary loss of nerve function due to a conduction block. Axonotmesis results from a disruption of the axon, with possible regeneration but slow and unpredictable recovery. The most severe form of nerve injury is referred to as Neurotmesis, permanent facial paralysis with surgical intervention. There are multiple ways the nerve can be injured during surgery: direct nerve trauma from a needle, intraneural hematoma formation, and toxicity from the local anesthetic. The nerve is particularly at risk when the procedure involves movement or removal of anatomical tissues near it.

Statistical Sources

A study was conducted with records of 15,846 patients involving surgeries related to the parotid gland, mastoid surgery, ear surgery, head and neck tumor resection, and thyroid surgery, with the parotid gland being the most frequently studied and the highest rate of facial nerve injury. Through the study, researchers found that facial nerve injury occurred in 4.6% of the surgeries. The percentage seems minuscule, but it corresponds to 736 patients, 736 unforeseen complications during surgery. Out of those 736 patients, 75 of them suffered from permanent facial nerve injuries following surgical procedures. The complication does not manifest solely as physical findings; facial paralysis can severely affect a person’s ability to connect with the world and those around them. In a separate study, it was found that nearly half (42.1%) of the patients with facial paralysis screened positive for at least mild depression, while the control group’s percentage was much lower at 8.1%. Facial nerve damage impacts much more than just the ability to smile– it can alter the joy one gets from life.

Prevention

As mentioned previously, the idea of preventing facial nerve injury during surgery is not unheard of in the medical field. Countless advancements in both technology and protocols have led to a decrease in the rate of facial paralysis over the decades. Intraoperative nerve monitoring (IONM) is a key factor in preventing injury. This technique allows surgeons to receive feedback on the nerve in real time– rather than discovering the damage after surgical completion. The functional feedback of the nerve allows the surgeon to adjust accordingly, such as using less traction, thermal protection, and more careful dissection. Another 2017 study utilized specific techniques to prevent facial nerve injury. The techniques included using higher magnification when working near the nerve, using blunter-tipped instruments to prevent sharp cuts against nerve fibers, and avoiding high settings on cautery tools. These protocols do not require any unattainable tools or resources; they simply require more delicacy when dealing with the facial nerve. After the surgical study, 0 patients suffered from permanent facial paralysis– only 17% experienced temporary facial weakness, which fully resolved over time. Through monitoring and the utilization of various precise surgical techniques, the risk of facial paralysis during surgery is arguably guaranteed to decrease. Despite no official protocol requiring surgeons to implement the techniques, further studies and education can be conducted to demonstrate their efficacy.

Sources:

Zamzam, S.M., Hassouna, M.S., Elsawy, M.K. et al. Otolaryngologists and iatrogenic facial nerve injury: a meta-analysis. Egypt J Otolaryngol 39, 71 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s43163-023-00440-0

Rosmaninho, A., Lobo, I., Caetano, M., Taipa, R., Magalhães, M., Costa, V., & Selores, M. (2012). Transient peripheral facial nerve paralysis after CO₂ laser therapy of an epidermal verrucous nevus. Dermatology Online Journal, 18(4), 15. https://escholarship.org/uc/item/2zx744fc

Nicoli, F., D’Ambrosia, C., Lazzeri, D., Orfaniotis, G., Ciudad, P., Maruccia, M., Shiun, L. T., Sacak, B., Chen, S.-H., & Chen, H.-C. (2017). Microsurgical dissection of facial nerve in parotidectomy: A discussion of techniques and long‑term results. Gland Surgery, 6(4), 308‑314. https://doi.org/10.21037/gs.2017.03.12

Dogiparthi, J., Teru, S. S., Lomiguen, C. M., & Chin, J. (2023). Iatrogenic Facial Nerve Injury in Head and Neck Surgery in the Presence of Intraoperative Facial

Nerve Monitoring With Electromyography: A Systematic Review. Cureus, 15(11), e48367. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.48367

Nellis, J. C., Ishii, M., Byrne, P. J., Boahene, K. D. O., Dey, J. K., & Ishii, L. E. (2017). Association Among Facial Paralysis, Depression, and Quality of Life in Facial Plastic Surgery Patients. JAMA facial plastic surgery, 19(3), 190–196. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamafacial.2016.1462