- Oct 21, 2025

Microsleep: The Hidden Danger of Sleep Deprivation

- Faisal Jahangiri

- neurophysiology, Blogs

- 0 comments

Introduction

Microsleep is a critical phenomenon characterized by brief, involuntary episodes of sleep that can last from 1 to 15 seconds. During these moments, the brain partially “shuts off,” even though the individual may appear fully awake, with eyes open and posture upright. These lapses are particularly common among those who are severely sleep-deprived or experiencing natural dips in their circadian rhythms, especially during monotonous activities like nighttime highway driving or repetitive tasks at work (Lim & Dinges, 2010; National Sleep Foundation, 2021).

During a microsleep episode, cognitive functions such as attention, perception, and reaction time decline sharply. This means individuals can easily miss critical visual or auditory cues without even realizing it (Anderson & Horne, 2006). The consequences are profound: drivers can drift out of their lane, pedestrians may overlook red lights, and workers can make errors in high-stakes situations, whether at a medical facility or on a factory line.

In this article, we will thoroughly explore the concept of microsleep, including its underlying causes, how to effectively recognize its signs, and the proactive steps you can take to prevent these dangerous lapses in consciousness. By understanding and addressing microsleep, you can enhance your safety and alertness in everyday life.

What Happens in the Brain During Microsleep?

Microsleeps are not simply “mini full sleeps.” Research clearly indicates that the brain can enter localized sleep-like activity, particularly when under sleep pressure (Vyazovskiy et al., 2011). In simple terms, some neurons or networks exhibit sleep-like firing patterns, while others remain alert and active (Nir et al., 2017). As sleep debt accumulates, the threshold for triggering these brief lapses decreases, leading to more frequent, slightly longer brief lapses (Lim & Dinges, 2010).

Electroencephalography (EEG) studies demonstrate that as vigilance declines, there is a noticeable increase in theta activity alongside a decrease in fast beta power, signifying a shift toward drowsiness (Corsi-Cabrera et al., 1992). Functional imaging further shows reduced activation in attention-related networks, particularly in the fronto-parietal regions, during sleep deprivation and task lapses (Chee & Choo, 2004). Together, these findings robustly support the assertion that microsleep represents a state of fragmented vigilance where performance-critical systems temporarily shut down, paving the way for potentially serious errors.

Causes and Risk Factors

The primary factor contributing to fatigue is insufficient sleep, with most adults requiring between 7 to 9 hours to function optimally (Hirshkowitz et al., 2015). Other significant contributors include circadian misalignment, such as those found in night shifts and jet lag, extended periods of focused attention, monotonous environments, certain medications (like sedatives and antihistamines), alcohol consumption, and untreated sleep disorders, including obstructive sleep apnea and narcolepsy (Institute of Medicine, 2006; Pack et al., 1995). Adolescents and young adults face heightened risks due to natural biological shifts toward later bedtimes and the prevalence of social and academic pressures (Carskadon, 2011).

The stakes are even higher in critical environments. Drowsy driving is responsible for thousands of crashes each year in the United States (Tefft, 2018), while in healthcare, fatigue contributes to an alarming increase in medical errors and needle-stick injuries (Rogers et al., 2004). Industrial accidents have likewise been connected to lapses in vigilance stemming from fatigue. Even among students, microsleeps undermine the ability to effectively encode information, exacerbating the detrimental effects of chronic sleep deprivation (Curcio et al., 2006).

Warning Signs to Watch For

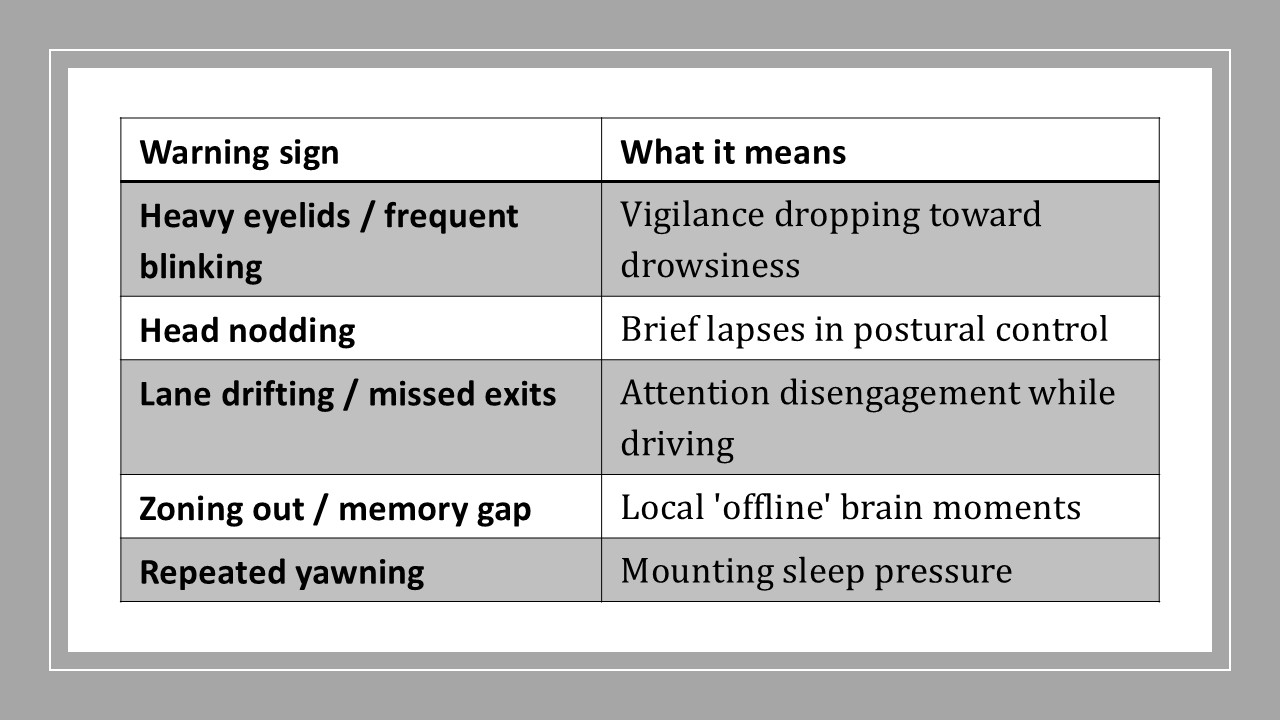

Several reliable indicators strongly signal that microsleep is imminent. These include repeated yawning, heavy eyelids, frequent blinking, difficulty maintaining head position, “zoning out,” missing crucial moments of a conversation or lecture, drifting in your lane, or failing to recall the last few miles driven (National Sleep Foundation, 2021). Advanced wearable devices and in-vehicle monitoring technologies are adept at detecting eyelid closures (PERCLOS), steering variability, and lane departures to effectively alert drivers. However, it’s essential to recognize that self-awareness remains a vital component in preventing these incidents (Jackson et al., 2013).

Why Microsleep Is Dangerous

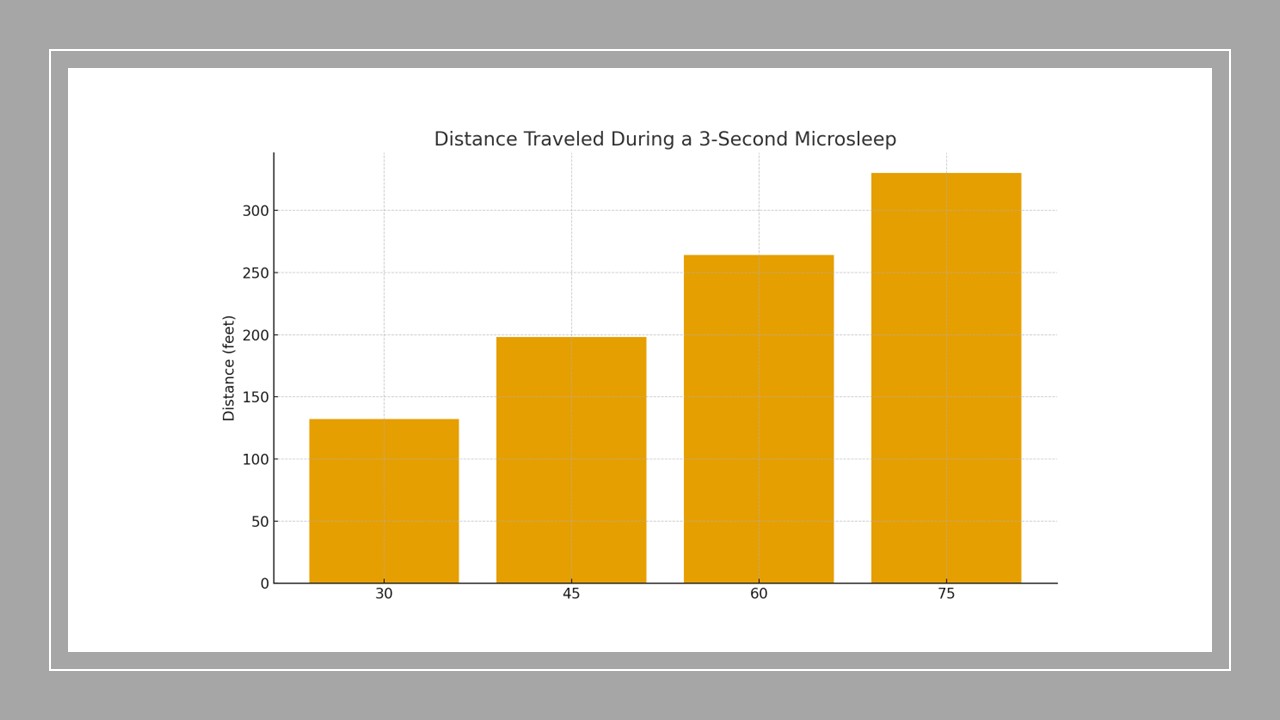

Microsleep poses a serious threat because it decreases your situational awareness without you even realizing it. Even a brief three seconds of inattention while driving at 60 mph can cause a vehicle to travel approximately 264 feet, which is nearly the length of a football field, during which the driver may not perceive hazards or adjust their course. In safety-critical professions, such as piloting, healthcare, and heavy equipment operation, just a few seconds can mean the difference between a near miss and a catastrophic incident (Rosekind et al., 1995).

It's important to understand that individuals often misjudge their own level of impairment; subjective feelings of sleepiness do not necessarily reflect actual declines in performance (Van Dongen et al., 2003). This means that you may feel "fine" while your brain is already on the verge of a lapse. While caffeine can temporarily mask feelings of drowsiness, it does not restore the essential neurocognitive functions compromised by sleep debt (Killgore, 2010).

Prevention and Practical Strategies

Address the root cause: prioritize your sleep and make it a consistent habit. Most adults need 7–9 hours of quality sleep, while teens should aim for 8–10 hours (Hirshkowitz et al., 2015; Paruthi et al., 2016). Combine this with robust sleep hygiene practices: establish a regular sleep schedule, limit evening caffeine and alcohol, reduce exposure to blue light before bedtime, and create a dark, cool, and quiet sleep environment.

If you find yourself driving while drowsy, the safest course of action is to pull over to a safe location and take a 15–20-minute nap (Tefft, 2018). Consider pairing this brief nap with caffeine for a quick boost (“nappuccino”) (Horne & Reyner, 1996). During long shifts, make it a point to schedule short breaks, rotate tasks to combat monotony, and strategically use bright light when working at night (Boivin & Boudreau, 2014). If you snore, experience breathing pauses at night, or wake up feeling unrefreshed after a full night’s sleep, take action and seek an assessment for sleep apnea; effective treatment is crucial for reducing daytime sleepiness and minimizing accident risk (Pack et al., 1995).

Key Takeaways

Microsleep refers to a brief, involuntary lapse in attention, often caused by sleep deprivation.

It poses a danger in situations that demand continuous focus, such as driving, medical care, and industrial operations.

Warning signs include heavy eyelids, nodding off, drifting out of your lane, and “zoning out.”

The best way to prevent microsleep is to get adequate, regular sleep, along with specific strategies tailored to the context, such as taking breaks, using bright lights, and taking short naps.

Figure 1. Distance traveled during a three‑second lapse (microsleep) at common highway speeds. Longer distances indicate greater exposure to hazards without awareness.

Table 1. Common warning signs of an impending microsleep and what they suggest.

Author Bio

Dr. Faisal R. Jahangiri is a clinician-educator specializing in neurophysiology and intraoperative neuromonitoring. He teaches students and healthcare professionals how to apply neuroscience to enhance patient safety and performance. When he is not in the operating room or teaching, he enjoys writing about practical brain science for everyday life.

References

Anderson, C., & Horne, J. A. (2006). Sleepiness enhances distraction during a monotonous task. Sleep, 29(4), 573–576.

Boivin, D. B., & Boudreau, P. (2014). Impacts of shift work on sleep and circadian rhythms. Pathologie Biologie, 62(5), 292–301.

Carskadon, M. A. (2011). Sleep in adolescents: The perfect storm. Pediatric Clinics, 58(3), 637–647.

Chee, M. W., & Choo, W. C. (2004). Functional imaging and behavioral correlates of capacity decline in visual short-term memory after sleep deprivation. PNAS, 101(9), 3752–3757.

Corsi-Cabrera, M., et al. (1992). Power and coherence of EEG alpha activity during sleep deprivation. Electroencephalography and Clinical Neurophysiology, 83(2), 71–77.

Curcio, G., Ferrara, M., & De Gennaro, L. (2006). Sleep loss, learning capacity and academic performance. Sleep Medicine Reviews, 10(5), 323–337.

Hirshkowitz, M., et al. (2015). National Sleep Foundation’s sleep time duration recommendations. Sleep Health, 1(1), 40–43.

Horne, J. A., & Reyner, L. A. (1996). Counteracting driver sleepiness: Effects of naps, caffeine, and placebo. Psychophysiology, 33(3), 306–309.

Institute of Medicine. (2006). Sleep Disorders and Sleep Deprivation: An Unmet Public Health Problem. National Academies Press.

Jackson, M. L., Howard, M. E., & Barnes, M. (2013). Cognition and daytime functioning in sleep-related breathing disorders. Progress in Brain Research, 190, 53–68.

Killgore, W. D. S. (2010). Effects of sleep deprivation on cognition. Progress in Brain Research, 185, 105–129.

Lim, J., & Dinges, D. F. (2010). A meta-analysis of the impact of short-term sleep deprivation on cognitive variables. Psychological Bulletin, 136(3), 375–389.

Nir, Y., et al. (2017). Selective neuronal lapses precede human cognitive lapses following sleep deprivation. Nature Medicine, 23(12), 1474–1480.

Pack, A. I., et al. (1995). Accident risk in sleepy obstructive sleep apnea patients. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, 152(1), 78–82.

Paruthi, S., et al. (2016). Recommended sleep duration for pediatric populations. Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine, 12(6), 785–786.

Rosekind, M. R., et al. (1995). Crew factors in flight operations IX: Effects of planned cockpit rest on crew performance and alertness in long-haul operations. NASA/TM.

Tefft, B. C. (2018). Prevalence of motor vehicle crashes involving drowsy drivers. AAA Foundation for Traffic Safety.

Van Dongen, H. P. A., Maislin, G., Mullington, J. M., & Dinges, D. F. (2003). The cumulative cost of additional wakefulness. Sleep, 26(2), 117–126.

Vyazovskiy, V. V., et al. (2011). Local sleep in awake rats. Nature, 472, 443–447