- Oct 24, 2025

From Wake-Up Tests to MEPs: The Evolution of Intraoperative Spinal Cord Monitoring

- Sheridan E. Fine, Faisal R. Jahangiri

- ionm, neuromonitoring, Blogs, mep

- 0 comments

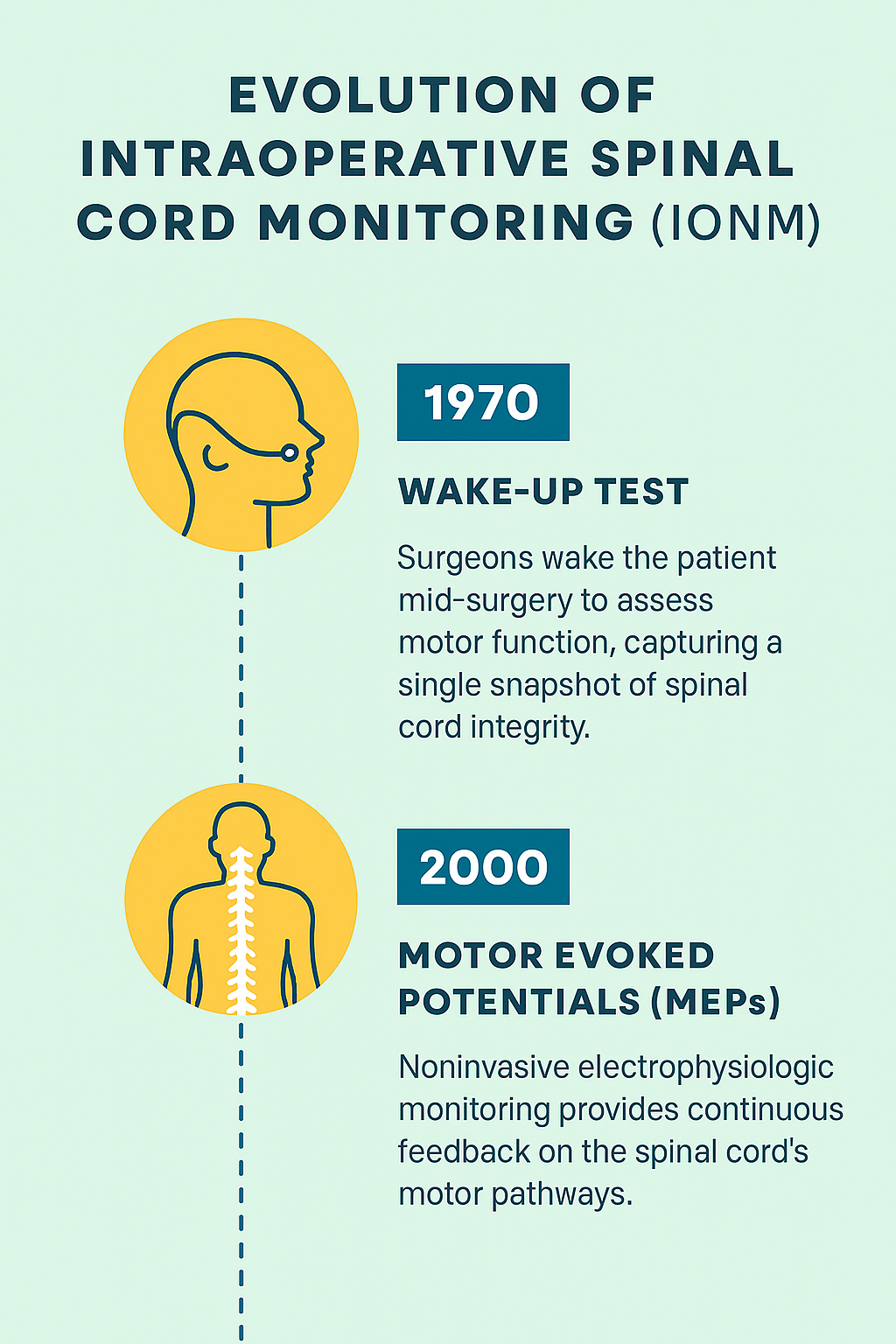

Intraoperative spinal cord monitoring (IONM) has undergone a profound transformation over the past several decades, evolving from intermittent, high-risk techniques to sophisticated, real-time neurophysiologic surveillance. Historically, the Stagnara wake-up test served as the standard method for assessing spinal cord integrity during surgery. This approach required partial arousal of the patient under anesthesia to elicit voluntary motor responses, an invasive and distressing process that offered limited sensitivity, delayed feedback, and no protection during critical phases of the procedure. The advent of Motor Evoked Potentials (MEPs) marked a turning point in spinal cord monitoring. By combining transcranial electrical stimulation with muscle response recording, MEPs enable continuous, real-time assessment of corticospinal tract function. This advancement allows for immediate detection of changes in motor pathway conductivity, facilitating timely surgical intervention and significantly reducing the risk of permanent neurological injury. This blog explores clinical and technological evolution from wake-up testing to MEP-based intraoperative neurophysiologic monitoring. Emphasis is placed on the underlying physiological mechanisms, anesthetic implications, and the interdisciplinary collaboration required to implement these techniques effectively in modern surgical practice. Keywords: Motor Evoked Potentials, intraoperative neurophysiologic monitoring, spinal cord integrity, anesthesia, corticospinal tract, wake-up test

Wake-Up Tests vs. MEPs: How Technology Transformed Spinal Cord Protection Over the past 50 years, the way we monitor the spinal cord during surgery has evolved dramatically from crude snapshots to sophisticated, real-time feedback. This transformation has not only improved surgical outcomes but also reshaped how we think about patient safety in the operating room.

The Wake-Up Test: A Bold but Blunt Tool

In the early days of spinal surgery, surgeons relied on the Stagnara wake-up test, a method that involved lightening anesthesia mid-procedure so the patient could respond to verbal commands. If the patient could move their feet, the spinal cord was presumed intact. If not, it was a red flag for possible injury.

While groundbreaking at the time, the wake-up test had serious limitations:

It was invasive and unsettling for patients.

It offered only a single moment of feedback, leaving long stretches of surgery unmonitored.

It introduced delays and risks, especially in complex procedures.

Enter MEPs: Real-Time Neurophysiologic Monitoring

Thanks to advances in neurophysiology and anesthetic techniques, we now have a far more elegant solution: Motor Evoked Potentials (MEPs). These allow surgeons to monitor the spinal cord’s motor pathways continuously throughout the operation.

MEPs work by stimulating the brain and recording muscle responses, providing:

Instant alerts if motor signals are disrupted ·

Continuous feedback rather than a one-time check

A non-invasive, patient-friendly alternative to the wake-up test

From Snapshot to Stream

MEPs represent a major leap forward in intraoperative neurophysiological monitoring (IONM). What was once a reactive, high-stakes moment has become a proactive, data-driven process. Surgeons can now detect and correct issues in real time before permanent damage occurs.

Introduced in the 1970s, the Stagnara wake-up test was a bold solution to a difficult problem: assessing spinal cord integrity during surgery. The technique involved lightening anesthesia mid-procedure to allow partial consciousness, enabling the surgeon to ask the patient to move their feet. A successful response suggested that the spinal cord was intact; failure to respond often meant the damage had already occurred.

Despite its ingenuity, the wake-up test came with serious drawbacks. Patients faced the risk of intraoperative awareness, hypertension, and even accidental extubation. And because it offered only a single moment of feedback, long stretches of surgery remained unmonitored, leaving the spinal cord vulnerable to undetected injury. For many years, it remained the standard of care simply because there was no better alternative. But as neurophysiology and anesthetic techniques advanced, the limitations of the wake-up test became increasingly clear. Researchers began searching for methods that could deliver objective, continuous monitoring without compromising anesthesia or patient safety. That research led to the development of Motor Evoked Potentials (MEPs), a breakthrough that would redefine intraoperative spinal cord protection.

Motor Evoked Potentials (MEPs) have provided a significant breakthrough in intraoperative monitoring. MEPs are generated by stimulating the motor cortex through electrodes placed on the scalp. These potentials are recorded as compound muscle action potentials (CMAPs) from limb muscles. The signals travel along the corticospinal tract, reflecting the functional integrity of motor pathways. A reduction in amplitude or a loss of signal can serve as an early indicator of issues such as cord compression, ischemia, or stretch. This real-time feedback enables the surgical team to adjust their techniques, instrumentation, or patient positioning before any irreversible injury occurs. The clinical importance of this responsiveness cannot be overstated, as it represents a shift from reactive assessment to proactive neuroprotection.

MEP monitoring is especially critical in high-risk spinal procedures, including scoliosis correction, spinal tumor resection, and thoracic trauma repair. In these scenarios, MEPs act as an early-warning system, enabling timely interventions that can potentially prevent permanent deficits. In contrast to the wake-up test, which only confirms loss of function after it has occurred, MEPs can detect changes within seconds, significantly enhancing the safety profile of spinal surgeries. However, the effectiveness of intraoperative neurophysiologic monitoring relies not only on technology but also on multidisciplinary collaboration. A neurophysiologist interprets MEP waveforms in real-time, while a technologist manages electrode placement and stimulation parameters. An anesthesiologist creates an appropriate pharmacological environment, as anesthetic agents can profoundly affect MEP amplitude and reliability. Guided by these signals, the surgeon can modify their techniques to reduce potential cord stress. Effective communication among all team members is vital, transforming electrophysiological data into immediate clinical action. This ensures that intraoperative alerts lead to reversible outcomes rather than permanent impairment.

Signal stability is essential for effective Motor Evoked Potential (MEP) monitoring during surgery. Factors such as anesthetic depth, temperature, blood pressure, and electrode configuration significantly impact recorded responses. While volatile anesthetics like sevoflurane and desflurane reduce cortical excitability, Total Intravenous Anesthesia (TIVA) with agents like propofol and short-acting opioids better preserves MEP amplitude. To obtain reliable recordings, it’s crucial to maintain normothermia and stable mean arterial pressure and to minimize the use of muscle relaxants. By following standardized protocols and utilizing expert interpretation, clinicians can confidently distinguish true neurological compromise from transient signal changes. In contemporary surgical practice, MEPs are effectively combined with Somatosensory Evoked Potentials (SSEPs) to create a robust multimodal intraoperative monitoring (IONM) system. MEPs assess descending motor pathways, while SSEPs evaluate ascending sensory tracts, offering a stable measure of spinal cord function even under anesthesia. This multimodality approach enhances the ability to distinguish between localized and global spinal cord issues, making it the standard of care in many surgical centers. Extensive clinical evidence supports its effectiveness in reducing postoperative neurological morbidity.

The shift from the Stagnara wake-up test to MEP-based monitoring reflects a significant advancement in surgical neurophysiology, fostering a continuous dialogue with the nervous system throughout the procedure. Ultimately, Motor Evoked Potentials exemplify the practical application of neurophysiological principles, enabling real-time interventions and drastically reducing the risk of permanent spinal cord injury. This evolution highlights a strong commitment to evidence-based neuroprotection, the result of decades of interdisciplinary collaboration.

References

Addanki, R. N. D., Ezhuvathra, P., Al-Qudah, A. M., Lee, B. B., Anetakis, K. M., Balzer, J. R., & Thirumala, P. D. (2025). Diagnostic accuracy of intraoperative neuromonitoring during non-tumor thoracic spine surgeries: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of clinical neuroscience: official journal of the Neurosurgical Society of Australasia, 141, 111567. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jocn.2025.111567

Doyal, A., Schoenherr, J. W., & Flynn, D. N. (2023). Motor Evoked Potential. In StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. Jahangiri, F. (2025). Module 3. Motor Evoked Potentials. ACN 7372 Evoked Potentials. MacDonald D. B. (2002). Safety of intraoperative transcranial electrical stimulation motor evoked potential monitoring. Journal of clinical neurophysiology: official publication of the American Electroencephalographic Society, 19(5), 416–429. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004691-200210000-00005

Nuwer, M. R., & Schrader, L. M. (2019). Spinal cord monitoring. Handbook of clinical neurology, 160, 329–344. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-444-64032-1.00021-7

Paunikar, S., Paul, A., Wanjari, D., & Alaspurkar, N. R. (2023). Neuromuscular Monitoring and Wake-Up Test During Scoliosis Surgery. Cureus, 15(8), e44046. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.44046 T

amaki, T., & Kubota, S. (2007). History of the development of intraoperative spinal cord monitoring. European spine journal: official publication of the European Spine Society, the European Spinal Deformity Society, and the European Section of the Cervical Spine Research Society, 16 Suppl 2(Suppl 2), S140–S146. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-007- 0416-9

Vauzelle, C., Stagnara, P., & Jouvinroux, P. (1973). Functional monitoring of spinal cord activity during spinal surgery. Clinical orthopaedics and related research, (93), 173–178. https://doi.org/10.1097/00003086-197306000-00017